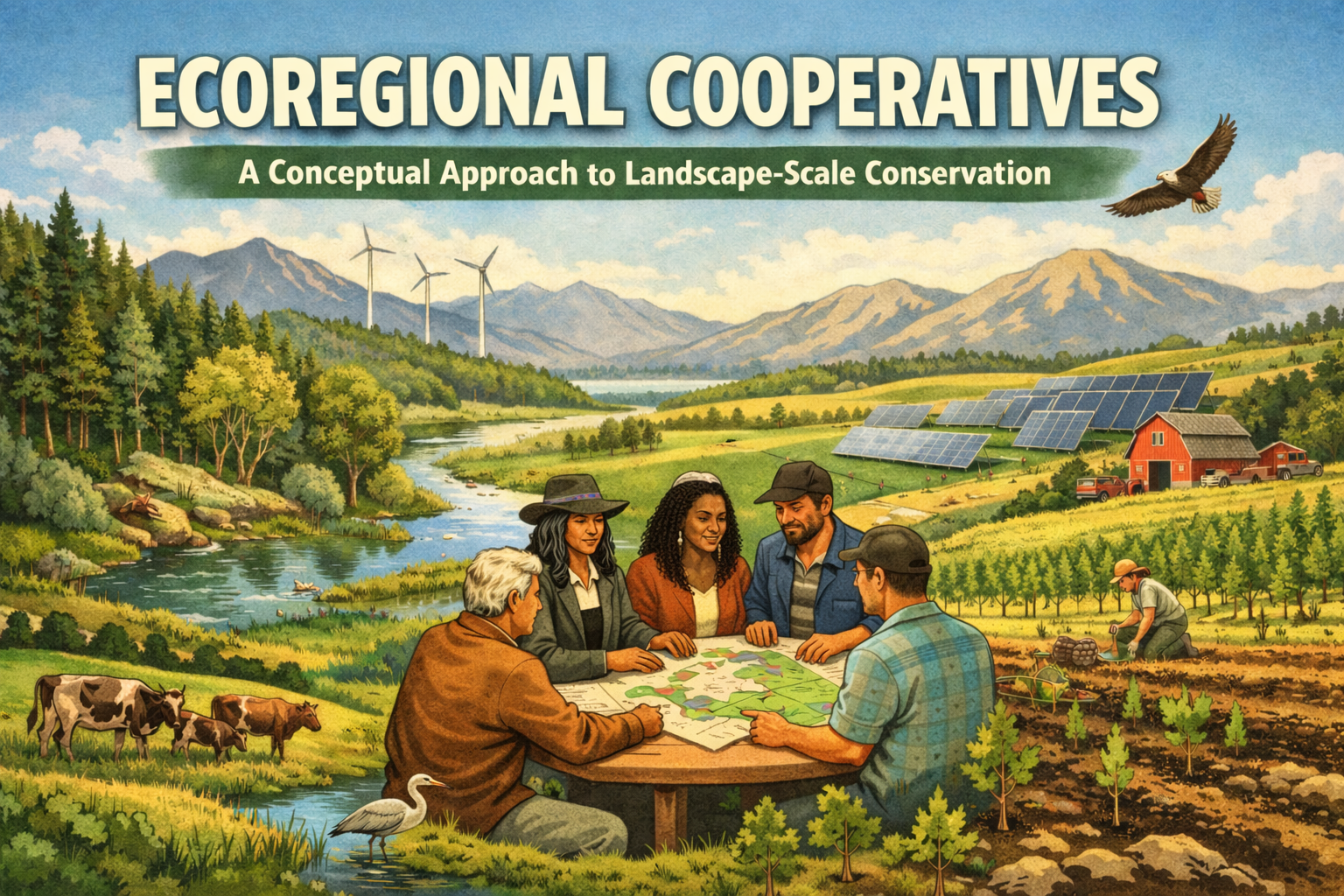

🌎Ecoregional Cooperatives: A Conceptual Approach to Landscape-Scale Conservation

Intro

This essay explores Ecoregional Cooperatives (ECOs) as a conceptual governance model for coordinating conservation and development at landscape scales. It is presented as an institutional design exploration, grounded in conservation science and cooperative governance theory, and is intentionally independent of any specific policy initiative or political context.

The discussion that follows treats ECOs not as a proposal to be implemented, but as a way of thinking about how institutional form, scale, and decision-making processes might be aligned with the ecological and governance challenges facing large, complex landscapes.

Ecoregional Cooperatives as an Institutional Design Concept

Efforts to address climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation are often organized through fragmented institutions and sector-specific programs. While these approaches have produced important local successes, they have struggled to operate at the spatial and temporal scales required by interlinked ecological challenges.

Increasingly, conservation science and practice point toward the need for governance structures that can function across jurisdictions, integrate diverse interests, and adapt over time.

One conceptual response to this challenge is the idea of Ecoregional Cooperatives (ECOs).

Defining the ECO Concept

ECOs are envisioned as locally led, landscape-scale cooperative organizations designed to support conservation and sustainable development within defined ecoregions. Rather than functioning as regulatory bodies or top-down programs, ECOs are conceived as coordinating platforms.

They are intended to bring together public agencies, Tribal governments, private landowners, community organizations, and other landscape stakeholders within a shared institutional framework. The focus is not on uniformity of interest, but on creating durable capacity for collaboration across differences.

The defining feature of the ECO concept is scale alignment. Ecoregions—defined by shared ecological characteristics rather than political boundaries—offer a more coherent unit for addressing issues such as habitat connectivity, watershed integrity, climate resilience, and land-use change.

ECOs are intentionally framed as a transformational approach to conservation and landscape governance. They begin from the premise that existing economic and institutional structures—largely sectoral, fragmented, and short-term—are not sufficient to sustain ecological integrity at scale. Rather than attempting to optimize within the status quo, the ECO concept explores how alternative organizational forms might reshape the relationship between conservation, land use, and economic activity across entire regions.

Core Functions of an Ecoregional Cooperative

In practice, the ECO concept centers on three interrelated functions.

1. Integrated Planning and Design

ECOs would support participatory planning and design processes that combine ecological data, spatial analysis, and stakeholder knowledge. These processes are intended to help identify conservation priorities, surface tradeoffs, and explore alternative futures across complex landscapes.

This function aligns closely with principles of Landscape Conservation Design (LCD), emphasizing transparency, scenario development, and adaptive decision-making rather than predetermined outcomes.

2. Program Coordination and Implementation Support

Rather than implementing projects directly, ECOs are envisioned as mechanisms for coordination and alignment. They would help connect initiatives already underway across sectors and jurisdictions within a shared design framework.

Examples could include habitat restoration, regenerative agriculture, renewable energy siting, climate adaptation measures, Indigenous-led land stewardship practices, or land protection efforts. The intent is not to standardize these activities, but to improve coherence and cumulative impact across the landscape.

Illustrative Activities and Initiatives

In practice, activities associated with an Ecoregional Cooperative would vary by ecological conditions, governance context, and stakeholder priorities. The ECO concept does not prescribe specific programs or interventions. Instead, it provides an institutional framework within which a wide range of conservation and land-use initiatives could be coordinated, aligned, and evaluated at the landscape-level.

Examples of activities that might be supported or coordinated through an ECO include:

Afforestation and restoration of degraded habitats, including efforts to reconnect fragmented ecosystems

Climate resilience and mitigation initiatives coordinated with regional innovation, research, or technology partnerships

Indigenous-led conservation practices, such as prescribed fire, species restoration, and culturally grounded land stewardship

Voluntary conservation projects on private lands, aligned with broader landscape objectives

Regenerative agriculture initiatives that integrate soil health, biodiversity, and working landscapes

Renewable energy siting and development coordinated through landscape-scale planning to reduce ecological conflict

Tribal, federal, and state land protection or management efforts, aligned across jurisdictions where possible

These examples are illustrative rather than exhaustive. They are intended to demonstrate the range of activities that could be brought into a shared design and governance framework, rather than to define a fixed program portfolio.

Taken together, these activities illustrate how conservation, land use, and economic livelihoods can be intentionally redesigned at ecoregional scales, rather than addressed through isolated or sector-specific interventions.

3. Supporting Sustainable Ecoregional Economies

Ecoregional Cooperatives are conceived not only as conservation coordination platforms, but as institutional vehicles for economic transformation at landscape scales. The ECO concept recognizes that biodiversity loss and climate change are inseparable from prevailing economic systems that reward extraction, fragmentation, and short-term returns. Addressing these challenges, therefore, requires rethinking how economic activity is organized, governed, and valued within ecoregions.

Rather than treating economic development as a separate objective, the ECO concept situates economic activity within landscape-scale conservation design, recognizing that livelihoods, land use, and ecological function are inseparable at ecoregional scales. In this framing, economic development is not an external pressure to be mitigated, but a core design variable.

Through cooperative ownership structures and multi-stakeholder governance, ECOs are intended to support forms of economic activity that are compatible with long-term ecological function. This may include the creation and coordination of jobs in habitat restoration, regenerative agriculture, ecosystem management, renewable energy development, monitoring and data services, and other conservation-aligned sectors. The emphasis is not on growth for its own sake, but on restructuring regional economies so that employment, investment, and ecological outcomes reinforce rather than undermine one another.

In this sense, ECOs can be understood as potential engines of ecoregional economic transformation. They offer a way to redirect capital, labor, and innovation toward activities that sustain ecosystem services, enhance resilience, and support communities over the long term. Whether such transformation is achievable depends on governance design, financing mechanisms, and sustained participation—but the ECO concept deliberately places economic change at the center of landscape-scale conservation thinking.

Governance, Conflict, and Tradeoffs

The ECO concept does not assume consensus or harmony among participants. Landscapes are shaped by competing values, histories, land uses, and power relationships. Conflict is an inherent feature of multi-stakeholder settings.

The cooperative model is intended to provide structured processes for deliberation, negotiation, and learning, rather than to eliminate disagreement. Its effectiveness would depend less on organizational form than on the quality of governance rules, facilitation capacity, and mechanisms for accountability.

Importantly, transformational approaches such as ECOs do not bypass political or economic conflict; they surface it. Efforts to redesign regional economies around conservation priorities inevitably challenge existing power structures, land-use norms, and investment patterns, making deliberative governance capacity central rather than ancillary.

ECOs as a Design Hypothesis

Ecoregional Cooperatives should be understood as a design hypothesis, not a prescription. They represent one possible way of organizing conservation and development efforts at scales commensurate with contemporary ecological challenges.

Whether such entities could function effectively would depend on context, governance capacity, financing, and sustained participation by landscape stakeholders. Within the broader framework explored in Designing Nature’s Half, ECOs serve as an illustrative example of how institutional design might be used to bridge ecological scale and governance structure.

ECOs are presented here as an idea to be examined, debated, advocated for, revised, or dismissed. They do not represent a settled solution, but a provocation: an invitation to consider whether alternative institutional designs could better align conservation outcomes, economic livelihoods, and governance at the scales where ecological change actually occurs.

Outro

Ecoregional Cooperatives are offered here as a design hypothesis, not a prescription. They represent one possible approach to organizing conservation and development efforts at scales that more closely match ecological processes, while acknowledging the institutional complexity and tradeoffs such efforts entail.

Within the broader framework of Designing Nature’s Half, this essay is intended to contribute to ongoing reflection about how governance structures shape conservation outcomes. Whether ECOs—or any similar model—could function effectively in practice depends on context, capacity, and the quality of the processes through which decisions are made. The purpose here is not to resolve those questions, but to surface them in a form that can be examined, tested, and refined over time.