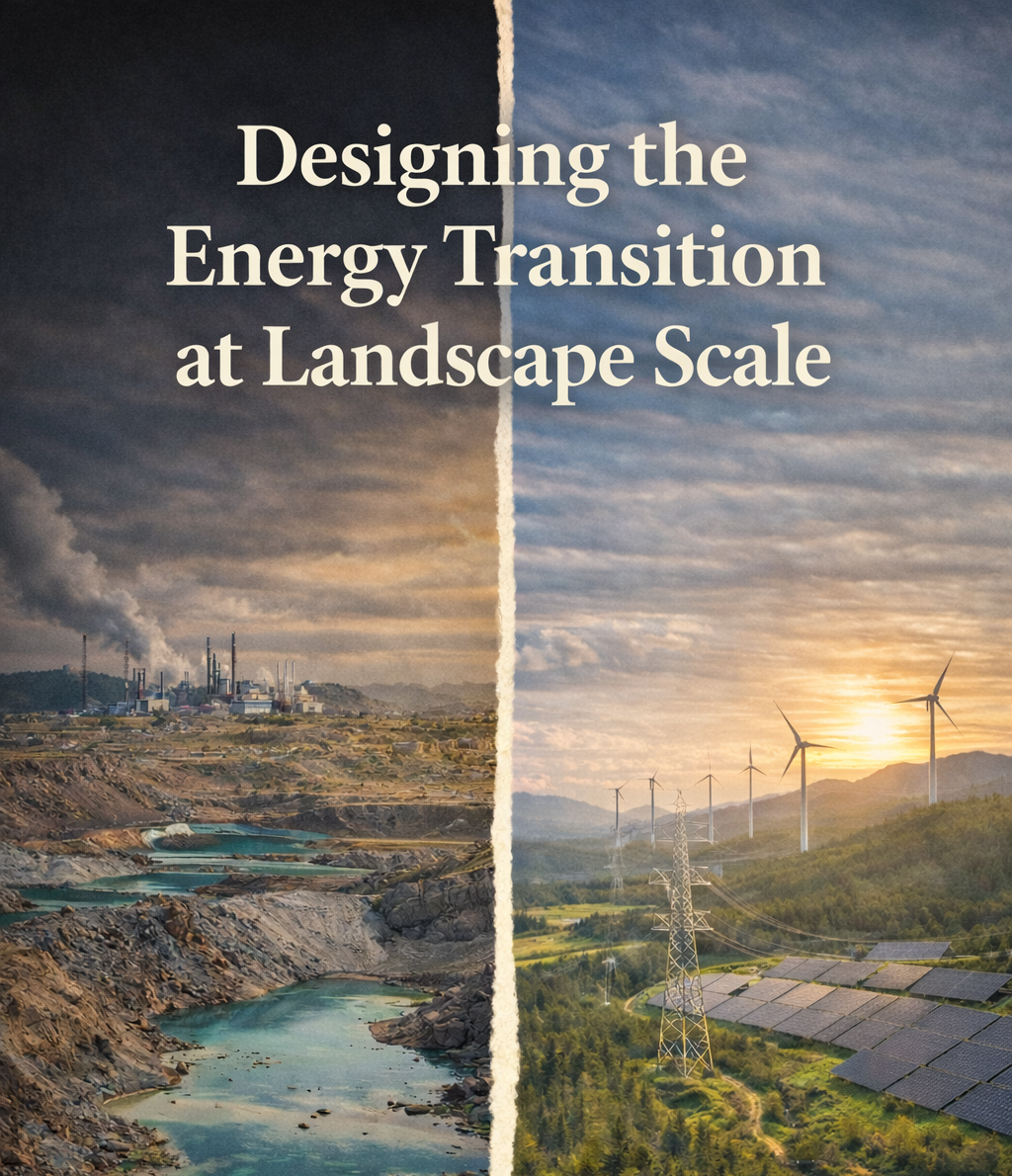

Designing the Energy Transition at Landscape Scale

Renewables have overtaken coal as the world’s largest source of electricity generation. China is building solar fields, wind farms, battery factories, and transmission corridors at historic speed. In the United States, federal climate regulation is weakening even as electricity demand continues to rise.

The energy transition is accelerating, but some landscapes and communities are carrying far more of its environmental and social burden than others.

Land is being converted. Minerals are being extracted. Water is being withdrawn. Transmission lines are expanding. These changes are not hypothetical; they are underway. The question is no longer whether the transition will occur. It is how the landscapes that sustain it are being designed.

As federal regulation recedes in the United States, the durability of the transition will depend on how infrastructure decisions are made across regions. Landscape conservation design (LCD) provides a framework for that landscape scale decision-making. Ecoregional Cooperatives (ECOs), as envisioned, provide a mechanism for applying LCD where projects are proposed and ecological resources are used and conserved.

China and the Scale of Accelerated Transformation

China offers the clearest contemporary example of what rapid energy transformation looks like under centralized state authority. In recent years, the country has led the world in new renewable energy deployment, electric vehicle production, battery manufacturing, and grid expansion. Growth in renewable electricity generation has been dramatic and sustained.

This acceleration did not happen organically. It reflects aligned finance, industrial planning, state-backed manufacturing, and coordinated infrastructure development. Policy direction and capital investment move together.

China demonstrates that large systems can be reorganized quickly when authority, capital, and planning are aligned. Centralized policy can compress timelines and accelerate build-out at national scale.

Every energy system — fossil or renewable — depends on material inputs and land use decisions. Solar arrays require land conversion. Wind facilities require transmission corridors. Manufacturing requires water, industrial sites, and mineral supply chains.

When transformation is organized primarily around production targets and strategic advantage, projects are sited and landscapes are converted quickly. The scale of build-out becomes the central metric of success.

Extraction Landscapes and the Material Foundations of Transition

Renewable energy technologies are often described as clean at the point of generation. Their supply chains, however, are materially intensive. Wind turbines rely on rare earth elements for magnets. Solar panels require polysilicon, silver, aluminum, and glass. Batteries depend on lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and manganese. Each of these materials originates in a specific landscape — mined, processed, and transported through industrial corridors that are rarely visible in discussions about climate targets.

China’s rare earth mining regions make this material reality difficult to ignore. In Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia and in the ion-adsorption clay deposits of southern China, extraction has generated vast tailings ponds and chemically treated leaching fields. Reporting from these regions documents contaminated water, damaged soils, and persistent waste streams. Processing one tonne of rare earth elements can generate roughly two thousand tonnes of toxic waste. These impacts are geographically concentrated, even when the resulting technologies are deployed across global markets.

This geography matters. The energy transition does not eliminate environmental burden; it redistributes it across regions and communities. Some areas host solar installations, transmission corridors, or battery plants. Others absorb mineral processing waste. Still others face groundwater depletion tied to energy-intensive manufacturing and related industrial growth. Deployment speed determines how quickly landscapes are altered — and how much time exists to evaluate alternatives.

When production targets dominate planning, siting decisions tend to prioritize speed, cost, and strategic leverage. Centralized authority can accelerate approvals and align finance, permitting, and industrial policy around rapid build-out. In the United States, energy projects typically move through a mix of federal, state, and local processes. The structure of decision-making, whether concentrated or dispersed, shapes how quickly infrastructure is built and how consistently environmental trade-offs are evaluated.

None of this negates the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It clarifies a design problem within the energy system transformation now underway. Expanding renewable generation and storage requires minerals, land conversion, water use, and transmission corridors. Electricity demand is rising, driven in part by new industrial loads and digital infrastructure. The question is whether these material demands are coordinated through transparent, regionally informed planning structures, or handled through a series of individual project approvals that distribute benefits widely while concentrating impacts in specific places.

Scale Without Design

Taken together, the global renewable milestone, China’s accelerated build-out, and the environmental costs of rare earth extraction reveal a consistent pattern. Energy systems can be reorganized quickly when capital, policy alignment, and industrial capacity converge. Speed, however, does not determine where land is converted, where waste is stored, or where water is withdrawn. Those outcomes are shaped by how decisions are structured. The central governance question is not whether transformation should proceed, but how the landscapes that absorb its material demands are selected, evaluated, and managed; and equally important, how those decisions are made.

Absent deliberate regional (i.e., landscape) design, energy infrastructure tends to advance through a sequence of individual proposals — a solar array here, a transmission corridor there, a processing facility elsewhere. Each project may meet its individual permit requirements. Yet the cumulative regional outcome often goes unexamined at the scale where ecological systems function and where people live and work. Over time, the pattern that emerges is not designed; it is assembled in an ad hoc fashion.

Landscape conservation design (LCD) addresses this structural gap. It operates at the scale where ecological processes unfold and where infrastructure decisions shape entire regions over time. Rather than evaluating projects solely within jurisdictional boundaries, LCD organizes ecological data, development pressure, infrastructure corridors, and community priorities in one regional analysis. The goal is not to slow transformation. It is to structure it so that trade-offs are visible before land is converted and impacts become difficult to reverse.

Frameworks, like landscape conservation design (LCD), do not implement themselves. In the United States, where federal climate regulations are weakening, the question is who convenes regional analysis and who has the authority and continuity to apply it over time. LCD provides the decision structure. Ecoregional Cooperatives (ECOs) could provide a governance mechanism capable of applying that structure across working lands, public lands, private lands, and infrastructure corridors.

ECOs, as envisioned, are designed to operate at the scale where ecological systems and major infrastructure projects intersect. They could convene state agencies, federal partners, Tribal governments, local communities, industry representatives, and nongovernmental organizations within a defined ecological region. By organizing data, mapping scenarios, and clarifying trade-offs before projects advance, ECOs shift decision-making from reactive permitting toward anticipatory regional design.

The energy transition will continue. Electricity demand will rise. Infrastructure will expand. The landscape will continue to be carved up into natural and developed patches. The design question is whether regions organize themselves to see these changes in advance — across watersheds, habitats, working lands, and communities — or whether siting decisions continue to unfold one permit at a time. The durability of the transition depends on how deliberately those landscapes are shaped.